Remote Australian project uses modelling, cost risk analysis to curb surprise spending

A recent decommissioning of seven wells in Australia's Puffin field required rigorous planning of equipment procurement, careful cost-risk analysis and round the clock response teams to negotiate unexpected issues and complete the campaign within 1% of the estimated cost, Claudio Pellegrini, Subsea Intervention Manager at AGR and project leader, said.

Related Articles

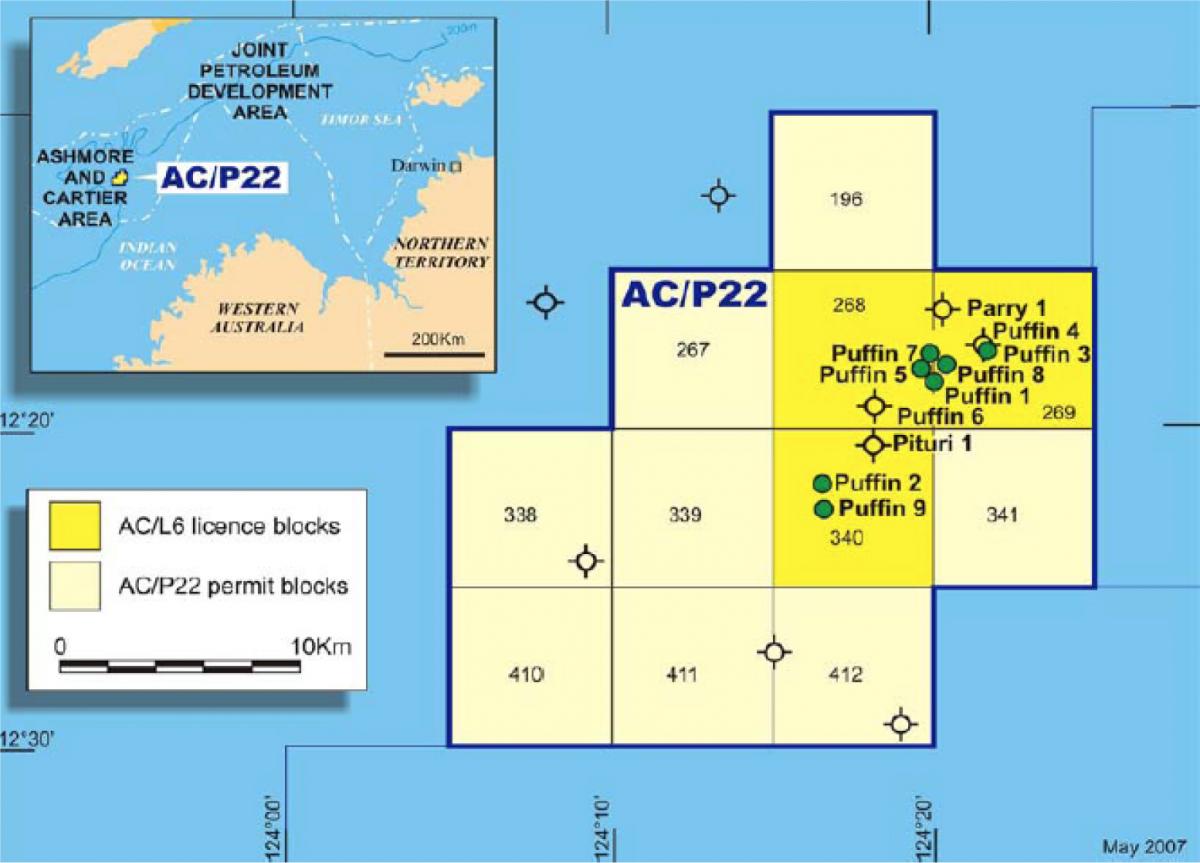

The decommissioning project, which took place in 2014 in the South Timor Sea, overcame challenges such as unexpected hydrocarbons in a shut-in well, dilapidated tubing, and antique subsea trees, Pellegrini told DecomWorld in an exclusive interview.

AGR, a global engineering and software company, conducted the decommissioning operations for Sinopec Oil and Gas Australia (SOGA), and the issues encountered highlight the importance of detailed planning and accessible data.

Detailed modelling and contingency planning meant the decommissioning project was completed within 1% of the Authorized For Expenditure (AFE) cost, set at around A$60 million ($43.1 million).

Source: AGR

AGR’s team in Australia were assigned to plan and execute the permanent well abandonment campaign of two shut-in production subsea wells and five suspended subsea wells in the Puffin field, located approximately 250km off the Australian coast.

Production from the field began in October 2007 through the use of a Floating Production, Storage and Offtake (FPSO) vessel tied to the Puffin-7 and -8 subsea wells. These wells required gas lift to produce oil. Production ceased in 2009.

Following a nine-month detailed planning phase, AGR executed operations between July and November 2014.

Fast response

A key challenge was the remoteness of the site – 700km from the port of mobilisation, Darwin, on Australia’s northern coast, and 4,042km by road to the main oil and gas hub of Perth, which is almost on the opposite side of the island continent.

Because of the remoteness of the location, the team had to be prepared to mobilise resources immediately, operating on a 24/7 schedule, said Pellegrini, who managed the project from AGR’s office in Perth.

In the field was a floating rig with accommodation for a hundred people, made up of subcontractors and key AGR personnel such as day and night drilling superintendents, subsea supervisors and an offshore logistics coordinator.

“It caused me a lot of sleepless nights because the phone would go off at any time, even the middle of the night,” he said.

Another significant challenge was presented by the fact that the subsea trees used on the two production wells had been spare trees from a different field and about 20 years old when installed. This meant the tools required to re-establish connection were also 20 years old, and had to be tracked down, purchased, refurbished and re-tested. Pellegrini said this was one of the most time consuming aspects of the planning phase.

Procuring other pieces of equipment also proved quite challenging. The BOP connector, weighing around 10 tonnes, had to be shipped from the US and so required detailed logistical planning.

Early modelling

The project team used AGR’s P1 software, developed in-house, for probabilistic cost and risk modelling. The software helped to plan the best approach to the visible challenges presented by the field.

Among these was the fact that all except one of the five suspended wells required the BOP stack to be run in order to pull the 9 5/8” slip and seal assembly to mitigate the risk of trapped annular gas.

This was further complicated by the fact that a mixture of different wellhead types existed in the field, with both types mixed in the two well clusters. Three of the suspended wells had H4 type profile wellheads while all others had Cameron hub type profiles, which meant that the BOP required a connector change-out during the campaign.

The two production wells had dual bore trees meaning a dual bore riser system had to be used, adding a large amount of equipment and complexity to the operations.

Furthermore, the production wells were designed as gas lift wells and approximately 1,600 psi gaslift gas was known to be present in the annulus, which would require flaring off.

Well P-7: nasty surprises

AGR sequenced operations such that the BOP connector change out could be carried out off the rig critical path. Nevertheless, AGR’s planning capabilities would be put to the test by nasty surprises in one of the production wells: P-7.

The first of these was the discovery of significant amounts of hydrocarbons in the well.

“Those wells were only two years in production, and not even particularly old, so the risk profile applied to it was quite low,” Pellegrini recalled. “We’d have anticipated gas in the annulus but not large amounts of hydrocarbons.”

A bleed-off package is an important part of any abandonment regime, and the project planners had to choose the packet size in accordance with risk. The cost difference between a large package and a smaller one was low enough to justify the larger one with a better risk profile.

“That proved crucial because when we connected to those wells we quite quickly found they had issues,” Pellegrini said. “We had to bleed off a lot of hydrocarbons. So much that we had to mobilise an additional surge tank to handle all the returns. If we’d gone with a smaller package we’d have had days of down-time.”

Tube erosion

The next headache came when numerous drift runs on P-7 failed to reach the target depth. “We thought maybe it was fish, as in dropped tools or materials, but when we tried to recover the tubing it came out in flakes, so it was clear the tubing had fallen apart,” Pellegrini said.

The team concluded that there had been a gas leak in the tubing that had eroded it from the inside.

“It shouldn’t have happened but we had a probability assigned to it,” said Pellegrini. “We had a lot of contingency equipment at the onshore base, ready to be called up if needed, and contingency procedures in place as well.”

The alternative solutions they devised meant they could complete the abandonment with minimal impact to the project schedule and budget.

In the end all seven wells were successfully plugged and abandoned.

Good data avoids surprises

Pellegrini noted that the unforeseeable issues they encountered at the Puffin field should hardly be considered surprises since good information on the construction and condition of wells is rare at the best of times.

The Puffin project benefited from electronic files and information can be much harder together for older fields.

“For wells drilled 15 or 20 years ago all the data is in hard copy in archives, or on VHS video tapes, or, if you’re lucky, those 3.5” floppy disks. It’s quite challenging to get the right level of information,” Pellegrini said.

When field ownership changes, as it did in Puffin’s case, from Melbourne-based AED to SOGA over 2008 and 2009, documentation can become even harder to find.

“Every time a company is sold, there are bits and pieces that get knocked off the shelves,” he said.

Miles Ponsonby, AGR’s Asia-Pacific region Business Development Manager, said Puffin could even be seen as a best-case scenario.

“The Puffin project is actually fairly representative of relatively new wells in Australia,” he said. “We’ve been looking at some wells here that were drilled in the 1960s, so information on those is likely to be in paper form but goodness knows where it is now. You could find yourself tracking down people who have retired to see if they remember what was done on the well.”

“I know of one example where all the well files were eaten by rats. Around the region there will be a huge range in the quality of the information available, from well-ordered archives to boxes of rat leftovers,” Ponsonby said.

Data in electronic form does not guarantee an easy ride either, however. “The data for Puffin, such as we had, was all electronic,” said Pellegrini. “But to get a handle on what is relevant is difficult because you’re sifting through hundreds of gigabytes and what you’re looking for may be incorrectly labelled and documents may not be consistently structured. It’s like looking for a needle in a haystack.”

“That’s why it’s crucial that you have experienced people, good financial risk management, tools that complement your team’s engineering excellence and a good, structured abandonment process to follow, ” Pellegrini said.