Quantifying value of disused offshore structures a ‘silver bullet’ for industry

The arguments for leaving offshore infrastructure in situ following decommissioning are well-known, although a North Sea ban on this practice proves external stakeholders are not easily convinced.

Related Articles

But what if the likely impact of such practices could be quantified in advance? That is the promise of net environmental benefits analysis (NEBA), according to the trio of Joseph P. Nicolette, Global Ecosystem Services Director of global environmental, engineering and health consultancy Ramboll Environ, Thomas Campbell, Partner at the international law firm Pillsbury Winthrop Shaw Pittman LLP, and Larry Johnson, Principal Engineer at BHP Billiton.

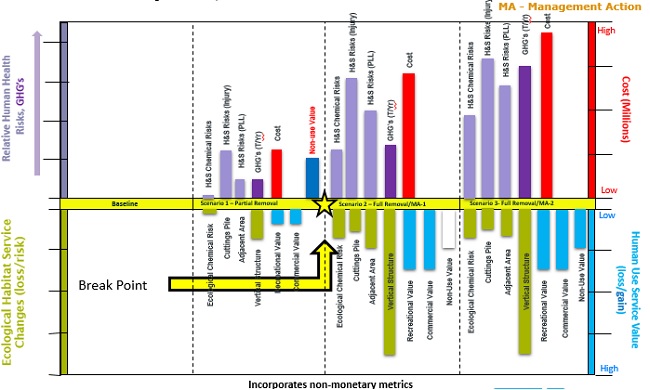

In oil-spill response NEBA provides a way to quantify and compare remedial options; in decommissioning it can be used to find the “break point” best option by quantifying and comparing the risks, benefits and trade-offs between alternatives, they told the 8th Decommissioning & Abandonment Summit in Houston last week.

This approach “is scientifically defensible and transparent, and we bring quantification into it so it doesn’t become a ‘he-said, she-said’ story,” explained Nicolette.

“It [NEBA] has a specific application here to help policymakers make those decisions as to the amount of decommissioning that is appropriate on a case-by-case basis,” added Campbell.

Measuring the results

Ramboll Environ has most recently applied the method to assess decommissioning projects with operators in the North Sea and Australia. In these cases, Nicolette said, the question was: what are the consequences of actions to remove or leave subsea equipment in place and do these consequences change between alternative scenarios?

Studies published by the US government have indicated a signification correlation between the removal of offshore platforms and significant declines in fisheries populations, he noted. But he said the NEBA approach takes into consideration more than just ecological resources: “It’s [also about understanding associated] changes in commercial fishing, any aesthetic value, recreational fishing, greenhouse-gas emissions, health and safety-implementation risks, potential loss of life from various alternatives, and injury risk.”

Factors taken into account by NEBA include: health and safety, technical feasibility, environmental impact, social, de-constructability, schedule, financial, energy consumption, waste management, sediment quality, marine mammals biological resources, air emissions (Source: Ramboll Environ)

Larry Johnson first heard about NEBA at last year’s Decommissioning & Abandonment Summit. He was so impressed by Nicolette and Campbell’s approach and insights gained when BHP applied the method to subsea components, that he joined them on stage at this year’s conference.

“The key point is that it [NEBA] is relative. You’re comparing cost to cost to cost, and risk to risk to risk. You’re not trying to monetize everything. You’re trying to put everything on a relative basis for comparison for alternatives in a holistic way,” Johnson explained.

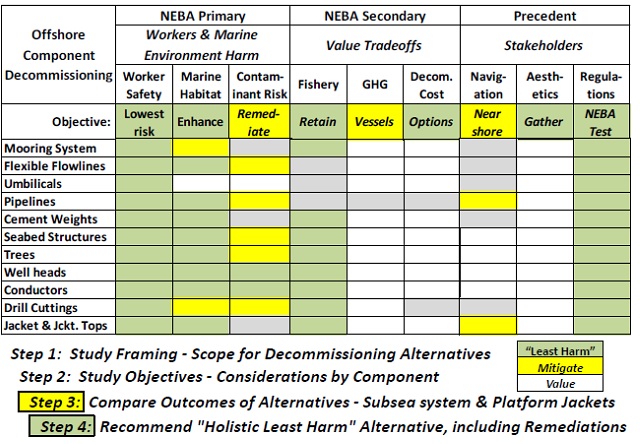

Each metric has a different weighting, he explained. The primary factors include worker safety, marine environmental habitat, and any contaminant risks left in the infrastructure. The second group are value trade-offs: “we can measure the impact on commercial fisheries, the value of commercial catch, recreational fishermen, greenhouse gas, and of course costs”. Third are stakeholders, precedents, aesthetics, and the impacts to navigation and shipping channels.

This generic table shows some of the components that may be assessed using NEBA analysis (Source: Courtesy of panelists)

“It’s really kind of cool that you can actually see the benefits and plot them all out,” Johnson said. “This is a flexible tool. You’re going to plug your wells. You’re going to remove your topsides. But everything in between: there are alternatives. Mooring systems: that could be everything from cables to buoys, and jackets, anything that holds up your topside; flexible flowlines, umbilicals, rigid pipelines, even cement weights – Joe [Nicolette] opened my eyes that while you’d think of those either of very little value, or possibly someone wants you to take them up to get a very clean seabed, they actually provide some ecological services, and they can be measured."

Johnson added that one cannot pre-suppose outcomes from NEBA, and stakeholders and operators must be prepared for “wherever the chips fall” in terms of site-specific and component-specific “least harm” outcomes form a “holistic” view.

From crisis to opportunity

Emphasizing NEBA’s flexibility, Johnson said he knew of a company planning to assess the impacts of removing the foundations of an onshore gas plant. This would come as no surprise to Nicolette or Campbell, who together with other representatives of industry and government developed NEBA following the 1989 Exxon Valdez oil spill in Prince William Sound, Alaska.

Nicolette co-authored the first formalized NEBA framework recognized by the US Environmental Protection Agency and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). Campbell was general counsel of the NOAA and a signatory to the $1 billion settlement between Exxon and the federal government. The precursor to NEBA, called habitat-equivalent analysis, emerged out of the clean-ups of the Exxon Valdez spill and Exxon Bayway Refinery spill in New Jersey, he recalled.

“What was created was a unit of measurement called a service-acre-year. If you have an oil spill [and] you end up with a natural recovery that causes an 800 service-acre-year loss, [and] the cleanup causes additional damage… what you need to do is simply find a restorational alternative that will create a benefit that will be greater than that was lost. You don’t need to monetize.”

With cooperation from operators including ARCO and Conoco [this being before the period of consolidation that led to ARCO’s merger into BP and the creation of ConocoPhillips], the findings were incorporated into regulations dealing with oil spills and environmental response, Campbell noted.

All three men believe NEBA will change the way stakeholders look at decommissioning, with Campbell predicting it will ultimately prove the misguidance of blanket removal: “I question the wisdom of our clean-seabed regulations… I would put forward a friendly hypothesis, and that is that the UK government will spend tens of billions of dollars reducing the ecological productivity of the North Sea – by [removing subsea structures associated with the decommissioning [process].”

Marine biologists have shown through their research that rig structures, platform structures and subsea infrastructure have “a complexity to them that creates valuable habitat,” he added.

“You have different ecosystems that operate at different depths, and they are co-dependent on each other, and they create a vitality in the middle of the ocean where no vitality existed before. We have good science that says that that is what’s happening… We’ve created a structure within which that science can be hung, and that decision makers, policy-makers can make objective – rather than subjective – decisions through an instrument that provides quantitative balancing to determine how much of a structure should in fact be removed.”

Responding to comments by another speaker about a lack of “silver bullets” in decommissioning, Johnson called NEBA a “silver bullet” for the industry. Speaking to DecomWorld following the conference, he remarked that this is “a credible, science-based, and transparent method to do our homework that regulators and stakeholders expect of operators, rather than falling back on precedent and individual opinions”.